The Life and Times of Alexander Wynch

The following are excerpts from books written about or around the lifetime of Alexander Wynch and pertaining to characters identified and explored herein.

The Church in Madras (Penny)

Extracts from The Church in Madras: Being the History of the Ecclesiastical and Missionary Action of the East India Company by Rev. Frank Penny LL.M. (Late Chaplain in H.M. Indian Service (Madras Establishment) published by John Murray, Albermarle Street 1904.

The Chaplains from 1647 to 1805

Robert Wynch was appointed (Chaplain) in 1731 and arrived the same year. In 1739 he married Margaret (Mansell) widow of Francis Rous of the Company’s Service, who was brother to Sir William Rous. She died in 1741. He went to Fort William in 1743 and died there in 1748[1] without issue. He was not a graduate of any British or Irish University[2]. He was probably nearly related to George Wynch of the Company’s Bengal Service. (p672)

From 1712 to 1746

At the beginning of the (following) year the Directors wrote[3]:-

“We are sorry for the death of Mr Smedley and have chosen Robert Wynch to succeed him, who takes his passage upon The George; he bears a very good character here, and we hope he will behave himself so in his station with you so as to merit your countenance and favour upon all occasions, his salary and gratuity is to commence at the time of his arrival,…”

Shortly afterwards the news of Mr Consett’s death reached the Directors. They referred to it in their next General Letter to Fort St George thus[4]:-

The death of Mr Consett, your Chaplain, is very much regretted, as it deprived you some time of the regular preaching of the Gospel; but we have supplied Mr Smedley’s place by sending to your assistance the Reverend Mr Wynch last year, and on The Prince of Orange comes the Reverend Mr Howard; and having so good characters of both these gentlemen; we don’t doubt but their arrival will be agreeable to you.”

Robert Wynch was entertained in October 1730, and was given a gratuity of £50,[5] a larger sum than had been given to any Chaplain before him except Consett, who was favoured for a special reason. One of the Company’s servants in the Bay at the beginning of the (18th) century was a George Wynch. Possibly Robert was the son of George, and was reaping the reward of his father’s faithful service; but no evidence has been found of this, nor indeed of Robert’s identity; for he was not a graduate of any British or Irish University. Eden Howard apparently received no gratuity.[6]

Wynch arrived at the Fort in July 1731 and was in sole charge for a year. When Eden Howard arrived in August 1732 the Governor and Council ordered Wynch to Fort St. David.[7] Here he remained till the end of the year. At the beginning of 1735 Wynch returned to England on private business.[8] Having finished his business he applied to the Directors to be allowed to return to Fort St. George; but stipulated that he should return to the place as he left it, that is, as Senior Chaplain. The Directors agreed and wrote thus[9]:-

“The Reverend Mr Wynch having desired to return as Chief Chaplain, we have granted his request; but as he came to England on his own private affairs, his salary must not commence till he arrives at Fort St. George.”

Wynch and Howard were together at Fort St. George from July 1736 till November 1742. The only incident on record during this period is the application of Wynch for house allowance in lieu of the lodgings which were occupied by others. The application was granted[10] on the ground that all the lodgings in the (inner) Fort were taken up by the covenanted servants and that it had been usual for one of the Chaplains to be furnished with lodgings by the Company. Wynch was on very friendly terms with a member of the Council named Francis Rous, a brother of Sir William Rous the head of the Suffolk family of that name[11]. Rous died in 1738, and Wynch married the widow[12] in the following year. She died at Fort St. George in 1741.

In 1738 Wynch applied to the Directors to be allowed to proceed to the bay as Chaplain. Fort St. George was still the most important settlement of the Company in the East; the request, therefore, strengthens the supposition that he had a family connection with Bengal, and that George Wynch of the Company’s Bengal Service was his father. The Directors permitted the transfer but ordered the he should remain at Fort St. George till a vacancy occurred.[13] This did not take place till 1742. The Directors then wrote:-

“We have appointed the Rev. Mr James Field to be one of your Chaplains; but Mr Wynch must have his option whether he will be Chaplain at your place or Bengal; and in case he chooses the Bay, or Mr Howard is come for England, Mr Field must officiate at your place; but otherwise he is to be one of our Chaplains in Bengal.”

The newly appointed Chaplain and the Company’s letter arrived in August 1743. Wynch at once applied to the Council to avail himself of the Company’s indulgence and to proceed to the Bay[14]. Permission was granted and he went. Eden Howard had already gone home[15]. And so James Field was left alone at Fort St. George. Robert Wynch died at Fort St. William in 1748[16]. He left no direct descendants; but Alexander Wynch, the Merchant Governor of Fort St. George, whose descendants have adorned various departments of the public service in the Presidency of Madras from the middle of the 18th Century to the present day, was his nephew. (pp158-160)

The SPCK from 1710 to 1750

July 1747: The Governor (Charles Floyer) produces the Charity Books for the year ending this day, balance being 889 pagodas; which he being desirous to quit himself of, Agreed that he make over the same to Alexander Wynch, the present Paymaster; that his bond be taken for 800 pagodas at 9 per cent; the odd money to remain in his hands to defray the expenses of the Charity School.

Oct 1748: Mr Prince being appointed Paymaster, Mr Wynch delivers in the Charity Books, which it is ordered to deliver to Mr Prince; that his bond be taken, etc.

Oct 1749: Mr Richard Prince delivers over to Mr Wynch in the same terms as above. (p198)

The Church Stock

Penny sets out a lengthy letter…

The date of this lengthy Despatch was the 17th June 1748; it arrived at Fort St David at the beginning of the following year. The Council welcomed the promise of receiving a copy of the St. Mary’s Church Ledger, and appointed a committee, consisting of Messieurs R. Prince, A. Wynch, and F. Westcott to examine the copy when received, and to carry out the directions received from the Court[17]. The proceedings of this committee are not recorded. (p213)

From 1746 to 1761

The French remained in possession (of Fort St George) nearly three years (from 1746 to 1749). Before the rendition they removed the guns to Pondicherry and many other things they had a fancy for; but the Commissioners appointed by Admiral Boscawen for receiving back the Fort – Major Stringer Lawrence, Messieurs Wynch and Westcott – were instructed to ask no questions and to make no difficulties. (p305)

In November 1755 the Churchwardens reported that they had Pagodas 7859 in hand, “with no prospect of employment of it”. In February 1757 this credit balance had increased to Pagodas 12000. It was resolved to offer this amount to the Governor and Council as a loan at 7 per cent. The offer was accepted; and in July 1761 the Vestry offered the Government Pagodas 4000 more. The Ministers and Churchwardens received bonds in exchange.[18] The careful nursing of this Fund for the benefit of the Church, the poor, and the School reflects the greatest credit on successive Ministers and Churchwardens of St. Mary’s. It has been already mentioned how this fund arose and grew; but one source of income has not been mentioned. The following letter to the Governor explains what it was[19]:-

“We beg leave to remind you that before the capture of this place all boats that were employed of a Sunday used to pay 6 fanams every trip to the School Stock which is now incorporated with the Church stock, the charitable expenses of which are lately increased by the erecting of a public Charity School here under the Rev. Mr Staveley, and by a monthly allowance to several of the European inhabitants.”

(signed) Sam Staveley, Minister

Alex. Wynch & Charles Bourchier, Churchwardens (pp313-314)

The St, Mary’s Vestry

“In September 1739 occurs this payment “paid Alexander Wynch for transcribing the Church Register, 50 pagodas”. This determines the date of the parchment register book. It is to be presumed that the older books were perishing, as paper books will in the climate of Madras; and that the new parchment book was intended to be a better means of preserving the important records they contained. Alexander Wynch was the nephew of Robert Wynch the Chaplain. It may have been a piece of nepotism which obtained for him the work; if so, it is certain that nepotism is not always a bad system; for the work of transcription is most carefully and excellently done.”

Gordon Campbell[20] had had occasion to look at the parish records of St Mary’s Church in Fort St George and wrote: “Two aspects of the registers became immediately obvious: the first was that they were parchment rather than paper; the second was that the entries from October 1680 to September 1739 were written in the same neat hand. These were clearly not original parish records but rather a later transcription. In fact the transcription had been prepared in 1739 by Alexander Wynch, then a little-known nephew of the garrison chaplain, but eventually to become Governor of Madras. The paper records had been succumbing to the climate of India, so Wynch had prepared a durable parchment copy, for which he was paid a fee of 50 pagodas”.

Penny sets out as an illustration a page of the Ledger for October 1739; in it are three entries as follows:

Mr Cradock rec’d int. at 7% on P2000

Robert Wynch do. P1300

Profit and Loss; pd. For burying Widow Wynch P1

There was a footnote against the last item that was, unfortunately, illegible. (p555)

Alexander Wynch was Churchwarden in 1754 and 1755 (p559)

Fort St George Madras (Penny)

Extracts from Fort St. George Madras by Fanny Emily Farr Penny published by Elibron Classics as an unabridged facsimile of the edition published in 1900 by Swan Sonnenschein & Co. London

Governors of Fort St. George

The first Governor was Mr Aaron Baker, appointed 1st Sept 1652.

Other (relevant) Governors were:

Mr Thomas Pitt (7th July 1698 to before 18th Sept 1709)

Mr George Morton Pitt (14th May 1730 to before 23rd Jan 1735)

Mr Charles Bourchier (25th Jan 1767 to before 31st Jan 1770)

Mr Alexander Wynch (2nd Feb 1773 to before 11th Dec 1775)

The latter dates are the dates of the appointment of their respective successors.

Reference to a Thomas Cooke as cash-keeper for the East India Company who was arrested when Hastings had required him to sell the Company’s silver. (p144)

George Morton Pitt, who became Governor in 1730, was born in Fort St. George and baptised in St. Mary’s Church in 1693. He was the son of John Pitt and Sarah Wavell[21] who were married at St. Mary’s and he was a distant cousin of Thomas Pitt the earlier Governor. He remained in power till 1735, when he left India for England. (p 151)

“In 1763 Robert Palk, who was in Deacon’s Orders and came out as a Chaplain to the Fort, but afterwards dropped his Holy Orders for the more lucrative service of the Company, became Governor. His name occurs frequently in the St. Mary’s registers, performing baptisms, marriages and burials soon after the restoration of the Fort to Admiral Boscawen. He was succeeded by Charles Bourchier in 1767, Josias Du Pré in 1770 and Alexander Wynch in 1773. All these men found the work of governing beyond their strength and were imbued with the notion that native princes must be subsidised with troops as well as money, and the consequence was that the Company soon became involved in war. In Du Pré’s time Hyder Ally dictated terms of peace at St. Thomas’ Mount to the Governor and Council, who placed themselves at his mercy. And in Wynch’s time Tanjore was unblushingly handed over by the Company’s troops to the Nabob. The Directors thought it was time to interfere; and they recalled Wynch.” (p 173)

Monuments of the OldCemetery

CASAMAJOR, NOAH[22]: died Sept 4th 1746, aged 45 years (he married Rebecca Powney in June 1736 and is entered in the Burial Register as Factor and the Registrar of the Mayor’s Court. His eldest son, James Henry, was baptised 3rd January 1746 in St Mary’s Church. Mrs Casamajor was the daughter of Captain John Powney and his wife Mary Horne (or Heron), and she was baptised in September 1715. (Page 191)

COOKE, Mr Francis: he served the Company for twelve years a Merchant and Assay Master. He died Feb 1711-12, aged thirty-nine years.

CRADOCK, THOMAS; son of Christopher and Florentina (sic.); he died Aug 13th 1712 in his fourth year. (Christopher Cradock married Florentina (sic.) Charleton in April 1707. Their son Christopher was baptised in 1710 and he married Grace Cook (sic.) in 1736. See Warre and Wynch. In 1735 Christopher Cradock commanded the Royal George, one of the Company’s ships). (Page 192)

WARRE, WILLIAM; Armiger, he died Third in Council May 6th 1715 aged about 35 years. He married (1) Ann Nicks in May 1704, and (2) Florentia Crodock March 1715. See Cradock. Ann Nicks was the daughter of John Nicks who married Catherine Barker Nov 11th 1680. Ann was baptised April 22nd 1689 and was buried March 24th 1711. John Nicks was in the Company’s service and went out to India in 1668. He had nine daughters and one son baptised at the Fort; the latter died in Dec 1686. Mrs Catherine Nicks died at Madras in Dec 1709 and John Nicks, March 14th 1711.

1716 William Warre of Madras

WYNCH, SOPHIA; wife of Alexander Wynch. She was one of the daughters of Edward Croke Esq., and died June 3rd, 1754, aged twenty-five years.

WYNCH, HARRY; son of Alexander Wynch and Sophia his wife. He died Dec 11th, 1754, aged one year and eight months. (Alexander Wynch became Governor of Madras. He married for his second wife, Florentia Cradock, in Dec 1754. See Warre and Cradock) (Page 201)

Alexander Wynch before becoming Governor of Madras

Penny notes that nothing is heard of Alexander Wynch until he became an unpaid assistant at Madras in 1730; whereafter, he wasn’t brought onto the List of Civil Servants until 1740. Perhaps his efforts (recorded above) in transcribing the old church register at St. Mary’s Church in Madras in 1739 had helped to convince the East India Company that he should be duly engaged. He became a Councillor at Fort St David in 1744, and in 1758 when the Fort yielded to the French he was serving as Deputy-Governor.

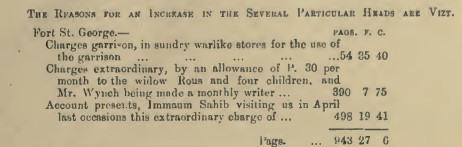

The snippet below[23] shows the increases in some elements of cost between the financial year 1st May 1737 to 30th April 1738 and the following year 1st May 1738 to 30th April 1739. This indicates the allowance to the widow of Francis Rous, a former functionary of the East India Company. It also indicates that Alexander Wynch had been taken on as a ‘monthly writer’.

This monthly writer role pre-dated his formal employment by the East India Company and subsequent entries through 1739 as shown in the entry for December 1739 when he was paid 10 pagodas (whilst his uncle Rev Robert Wynch was paid 7 pagodas in the month for house rent and Margaret Rous was paid 20 pagodas allowance money to 4 children of Mr Rous deceased).

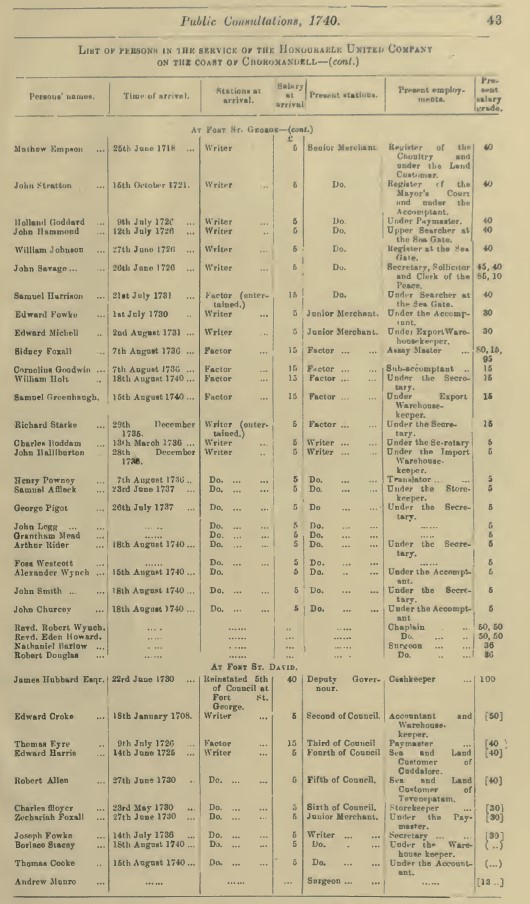

The records show that Alexander became an employee of the East India Company on the 15th August 1740 as a Writer working for the Accountant (as shown below).

The Vestiges of Madras describe the relationship between Alexander and his uncle as follows:

“Wynch – The Rev. Robert Wynch, Chaplain of Fort St. George, who went home with G.M.Pitt in 1735, soon obtained permission to return to Madras. In 1739 he married Margaret, widow of the Councillor Francis Rous, and in 1743 he was at his own request, ttransferred to Bengal. Alexander Wynch, who was perhaps a nephew of the chaplain, is first mentioned in August, 1738, when he was entertained as a monthly writer after serving four years as unpaid assistant to the Secretary[24]. In 1740 he was brought onto the permanent list, and in the following January he named as his security ‘Mr. William Wynch, who, he hopes, will be able to engage some other person to stand with him in England, from whence he came so yound as to have no acquaintance there of whom to ask that favour.’[25] Alexander was admitted to the Council of Fort St. David in 1744, and in 1758, when that place was given up to the French, he was officiating Deputy Governor. Wynch was made prisoner of war, resigned the service, and went to England; but in 1768 he was reappointed, and became Chief at Masullipatam. From 1773 to 1775 he served as Governor of Fort st. George. He married, first, Sophia,[26] daughter of Edward Croke, a member of the Council of Fort St. David, and, secondly, in 1754, Florentia Cradock, daughter probably of Christopher Cradock, jun. The lady known for many years in Calcutta society as ‘Begum Johnson’ was a sister of the first Mrs Wynch. Alexander Wynch, who died in Harley Street in May, 1781,[27] gave three sons, William, George, and John, to the Madras Civil Service. William Wynch joined in 1766, and in 1784 was a Commissioner of the Board of Accounts. George Wynch became a Writer in 1773, was Collector of Kărũr in 1791, and appears to have retired in 1798. John Wynch, first a free merchant, was appointed to the service in 1775, and in 1797 was Paymaster at Vellore. Alexander Wynch, who is believed to have been another son of the Governor, entered the Madras Army in 1768, rose to the rank of Colonel, and retired in 1800. The next generation saw a John Wynch in the Madras Artillery. He entered in 1814, and still held the rank of Captain in 1825. The Wynch family is still represented in the Indian Civil Service in the Southern Presidency.”

The reference in the above extract to the surrender of Fort St. David to the French was an episode about which further published accounts are available. Set out below is an account of the surrender of Fort St. David to the French army under the command of General Lally in 1758.

Surrender of Fort St. David by Alexander Wynch (1758)

“The English were greatly deficient in regard to land forces, and the re-establishing of Bengal had greatly exhausted them of men on the coast of Coromandel, where all their military force consisted of no more than 700 effective troops; while M. Lally was at the head of 5000 men well disciplined and officered; so that it is no wonder Fort St. David fell a sacrifice.

“General Lally marched from Pondicherry to Fort St. David, with an army of 3500 Europeans and a large body of sepoys. Their vanguard consisted of the French horse, a battalion of the regiment of Lorrain, 200 of the company’s troops, and 100 artillery-men, with eight pieces of cannon accompanied by 4000 sepoys, entered the district of Fort St. David on the 29th April. They plundered the villages, and destroyed the outposts until they came to Cuddalore, which they invested and obliged to surrender on the 3rd may, with permission for the garrison to retreat to Fort St. David with their arms.

“The French then began the siege of Fort St. David, and fired upon it from Cuddalore on the 16th with two guns; as also with five mortars from the new town on the 17th; but on the 26th, a battery was opened at the distance of between eight and nine hundred yards west; another of nine guns and three mortars between seven and eight hundred yards north; and another of four guns at about the same distance to the north-east.

“The country troops and artificers deserted the place, which was badly fortified, and poorly defended. No breach was made; but thirty guns and carriages were dismounted and disabled; besides many of the parapets, platforms and other works were destroyed by the shot and shells. Water was difficult to be got, as the reservoirs had suffered by the bombardment, and the best well was destroyed. Ammunition grew also scarce, as it had been inconsiderately fired away before the besiegers had erected their batteries.

“Major Polier commanded in the fort, and finding it untenable, he desired Alexander Wynch, Esquire, who acted as deputy-governor, to hold a council of war; which was accordingly done, when it was unanimously agreed, by Mr Wynch and the gentlemen of the council, to surrender the place upon terms of capitulation. The principal articles granted by general Lally were: “That the garrison should be allowed the honours of war; be exchanged; and allowed to carry with them their baggage and effects; that care should be taken of the sick and wounded; and deserters should be pardoned upon condition of returning to their colours: but that two commissaries should be appointed and remain to deliver up the magazines and military stores; as also to shew the French all the mines and subterraneous works.” These articles were signed on 2nd June by Ar. Wynch; P. Polier de Bottens; and Rich. Fairfield; on the part of the English and by Lally; on the French part.”

Alexander left India following that incident and we have very little insight into Alexander’s life and works until he became Governor of Madras although we do know that some of his children were born in England.

Alexander Wynch as Governor of Madras

Alexander Wynch became Governor of Madras with effect from 2nd February 1773 until he was recalled in 1775.

The incident that led to his recall is summarised here in which the Court decision is spelt out in brief and Alexander’s response is set out in detail.

Alexander Wynch in England

During his absence from india between 1758 and 1768, and after his return in 1776, Alexander maintained a house or houses in England.

At the time of George Pitt Cradock’s will (29th December 1763), for example, his brother in law bequeathed the residue of his estate to “my loving sister, Florentia Wynch, wife of Alexander Wynch of Bilton Park in the County of York” (located near Harrogate and Knaresborough and where the keeper of the King’s Castle at Knaresborough, Peter Slingsby, once resided, and shown below as it looked in 1623).[28]

Three of Alexander’s children were born in England during Alexander’s break from the Honourable East India Company’s service: Florentia, James and Margery.

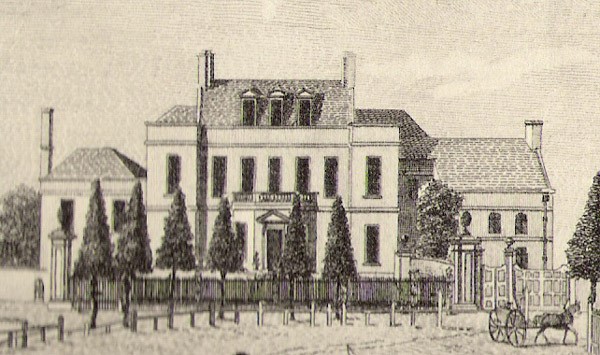

He had a lease of Gifford Lodge in Twickenham (seen below in 1753) from the Marchioness of Tweeddale from 1776 following his recall from Madras.

Alexander also took a house in Upper Harley Street. It was from there that his daughter Frances eloped with the unreliable son and heir of Sir William Twysden of Roydon to marry at Gretna Green, she at the age of 15, and he fleeing to France immediately afterwards to escape his creditors. Perhaps he had been looking to the dowry of £10,000 (British pounds) that Alexander typically paid to each of his children upon the coming of age or marriage.

Wynch then moved to Westhorpe House in Marlow[29], where he died in 1781. George III visited Westhorpe in 1781 and bought some of the furniture to give to Queen Caroline. It came into the possession of the Prince of Wales and was installed in the Pavilion at Brighton before finding its way to Buckingham Palace where today it forms a part of the Royal collection.

”While traveling in Buckinghamshire in October 1781, the king stopped at Westhorpe House near Marlow, the home of the recently deceased Alexander Wynch (governor of Madras, 1773-5), and was shown a quantity of ivory furniture by the auctioneer James Christie,” Jonathan Marsden writes in ”George III and Queen Charlotte: Patronage, Collecting and Court Taste” (Royal Collection Publications, 2004). ”The king purchased a settee, 10 chairs and two miniature bureau-cabinets.”

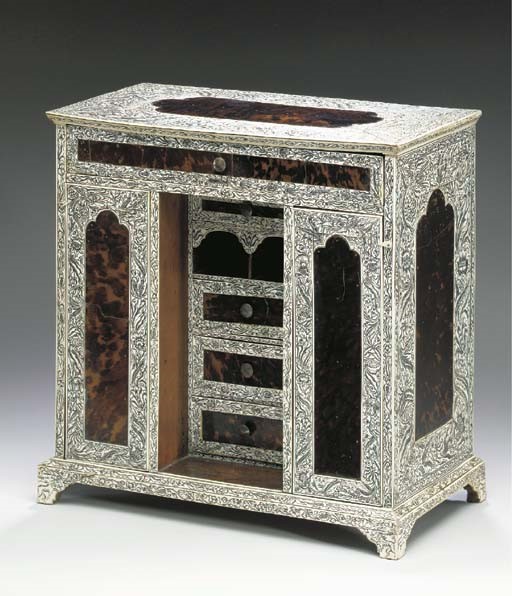

A similar lot sold at Christies in New York in 2002 for $14,340; it was described (pictured above) as:

“AN ANGLO-INDIAN ENGRAVED IVORY AND TORTOISESHELL MINIATURE KNEEHOLE DESK**

Vizigapatam, late 18th century

The rectangular top with central lozenge reserve overhanging a long frieze drawer, the kneehole with four sandlewood-lined drawers and two pigeonholes flanked by a removable panel enclosing four further drawers and two pigeonholes, each side similarly with a lozenge reserve, on bracket feet, with scrolling foliate-engraved borders and moldings overall, with the remnants of a printed BADA label to the underside

17in. (43cm.) high, 16¾in. (42.5cm.) wide, 8¾in. (22cm.) deep

Special Notice

Notice Regarding the Sale of Ivory and Tortoiseshell Prospective purchasers are advised that several countries prohibit the importation of property containing ivory or tortoiseshell. Accordingly, prospective purchasers should familiarize themselves with relevant customs regulations prior to bidding if they intend to import this lot into another country.

Lot Notes

This miniature desk, designed in the distinctive English manner of the 1720s and decorated with engraved scrolling floral vines, is part of a group of exotic ivory-veneered furniture probably executed under the direction of the Dutch and English East India Companies at Vizagapatam, a port on the Coromandel Coast in southern India, in the second half of the 18th century. Two miniature cabinets of circa 1770 brought to England by Alexander Wynch, Governor of Fort St. George from 1773 to 1775 and now in the Royal Collection display similar decoration (one illustrated in J. Harris et al, Buckingham Palace and Its Treasures, New York, 1968, p.126). A second miniature kneehole desk with blank ivory panels sold in these Rooms, 30 January 1993, lot 138 ($24,200), making for a strong comparison in form and in the similarly engraved ivory borders.

By the 1760s, Vizigapatam artisans were regularly decorating such miniature furniture with engraved architectural scenes or more entertaining vignettes based loosely on European print sources. This type of decoration can be seen in miniature bureau-cabinet of circa 1780-90 in the Peabody Essex Museum (A. Jaffer, Furniture from British Indian and Ceylon, 2001, cat. no. 46, pp. 200-203 and also in ‘Art & the East India Trade’, Exhibition Catalogue, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1970, fig. 21). Other examples include one in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, of similar date (illustrated in Jaffer, op. cit., fig. 93, p. 202).

While the decoration is representative of many objects made at the time, the use of tortoiseshell panels points to a distinct sub-group. Perhaps the most pertinent related example is a table cabinet dated to the late 18th century with tortoiseshell-veneered reserves to each drawer front and panel sold Christie’s London, 27 June 1983, lot 62A”

A note of some of Alexander’s possessions is contained in references in the Royal collection such as:

Indian (Vizagapatam)

Settee c.1770

Sandalwood veneered with ivory,

engraved and inlaid

101.0 x 184.0 x 82.5 cm

Alexander Wynch (d. 1781); his sale, Christie and Ansell, Westhorpe House, 6 October 1781, lot 54; purchased by George III (48 gns.) and presented to Queen Charlotte; her sale, Christie‘s, London, 7-10 May 1819, lot 107; purchased by Loving on behalf of the Prince Regent (£52 10s)[30]

It was not just furniture that was sold following Alexander’s death:

“A catalogue of all the genuine stock of excellent wines, consisting of about 400 dozen of oriental madeira, near 200 dozen of fine old red port, red and white constantia, old arrack, &c. Also, some valuable jewels, two gold repeating watches, … and other effects, of Alexander Wynch, Esq; deceased, which will be sold by auction, by Mess. Christie and Ansell, (by order of the executors) … on Monday, November 5, 1781, and two following days (catalogue held in the Library of University College London)”

It is also noted that, in Alexander’s will, he leaves each of his daughters not yet of age (namely, Frances and Margery), ten thousand pounds each in 1781.

1781 Alexander Wynch

[1] Hyde’s Parochial Annals of Bengal pp96-98

[2] There is reference to a Robert Wynch being a graduate of Cambridge at about the right time

Cambridge University Alumni, 1261-1900: Robert Wynch, EmmanuelCollege, pens. At Emmanuel, May 8, 1717. of Middlesex. One of these names chaplain to the East India Company, 1731. Died at Fort William, 1748 (F.Penny)

[3] Despatch 12 Feb 1730-1, para 57

[4] Despatch 11 Feb 1731-2, para 78

[5] Court Minutes, 15 Dec 1730

[6] Court Minutes, 26 Jan 1730-1

[7] Consultations, 14 Aug 1732, and letter, 28 Aug 1732, para 79

[8] Consultations, 23 Jan 1734-5

[9] Despatch, 12 Dec 1735, para 23

[10] Consultations, 21 Sept 1737

[11] This is unlikely as no connection has been shown

[12] Mistress Margaret Rous

[13] Despatch, Jan 1738-9

[14] Consultations, 29 Aug 1743

[15] Consultations, 15 Sept 1742

[16] Hyde’s Parochial Annals of Bengal pp97-8

[17] Fort St. David Consultations, March 1748-9

[18] Consultations, October 1761

[19] Consultations, May 1754

[20] Milton Quarterly 31.2 (1997) pp61-63

[21] Née Charlton or Charleton (see later references to Sarah Pitt)

[22] IGI notes that his parents were Luiz Juan Casamajor and Clemence Lapeyre, that he was born in 23rd December 1702 in Bristol, was baptised at the French Episcopal Church in Bristol on 1st January 1703 and married Rebecca Powney at Fort St. David on 15th June 1736. He was presumably the father of John Casamajor who married Hannah Cradock (daughter of Christopher Cradock and Florentia Charlton).

[23] From: Records of Fort St. George; Selections from Public Consultations, Letters from Fort St. George, and Fort St. David Consultations, 1740 (published by the Government Superintendent Press of Madras, 1916)

[24] This suggests Alexendar was out in India by the time he was fourteen years of age.

[25] “P.C., vol. lxxi., 3rd Jan. 17401. In January, 1742, we find the Rev. Robert Wynch remitting £100 to William Wynch. It is conjectured that the latter was Alexander’s father and Robert’s brother” (in fact it appears William Wynch is Alexander’s other uncle alongside Rev. Robert Wynch).

[26] “She died in 1754, and her tombstone is in St. Mary’s pavement.”

[27] “Bills of Sale, etc., No. 76, dated 22nd Feb., 1785.”

[28] Though much of what can be seen externally today dates from when the outside was re-modelled in the Tudor style during the second half of the 19th century, parts of the interior date from the late 14th century.

It was in 1380 that John of Gaunt, Lord of Knaresborough and son of Edward III, ordered the building of a new hunting lodge in Bilton Park that was held by the Crown until the park was sold by Charles I in 1628. Interestingly, parts of that original 1380 building are still in use today.

Previous to this sale the lodge which evolved into Bilton Hall was held from the middle of the 16th century by members of the Slingsby family who were, at the time, possibly the most powerful family in the district. However, in 1615 charges were levied against Henry Slingsby, keeper of Bilton Park, concerning the dilapidated state of the park and the diminishing number of deer held in the park and this led to the family’s eviction and the lease was passed to Esme Stuart, Lord Aubingy.

Three years after Charles I sold the park, Bilton Hall was bought by Thomas Stockdale, a staunch parliamentarian, a friend of Thomas Fairfax, and a bitter political rival of the Slingsbys. Thomas Stockdale represented Knaresborough as Member of Parliament throughout the civil war years and was followed by his son William and later Christopher, who stood until 1713.

The last Stockdale to own Bilton Hall was Thomas, who mortgaged Bilton Park in 1720 to raise £1,000 to invest in the ill-fated South Sea company.

Unfortunately, like so many others, when the South Sea bubble burst, the Stockdales lost everything and were forced to leave, eventually settling in America.

In 1742 the estate passed into the hands of the Watson family, who remained here for many years and presumably leased the property to Alexander Wynch.

[29] Alexander Wynch insured the property against fire: 1780 Sun Fire Insurance 11936/284/432163 15 Aug 1780 (Alexander Wynch of Westhorpe parish of Little Marlow Esq)

[30] Catalogue entry adapted from George III & Queen Charlotte: Patronage, Collecting and Court Taste, London, 2004